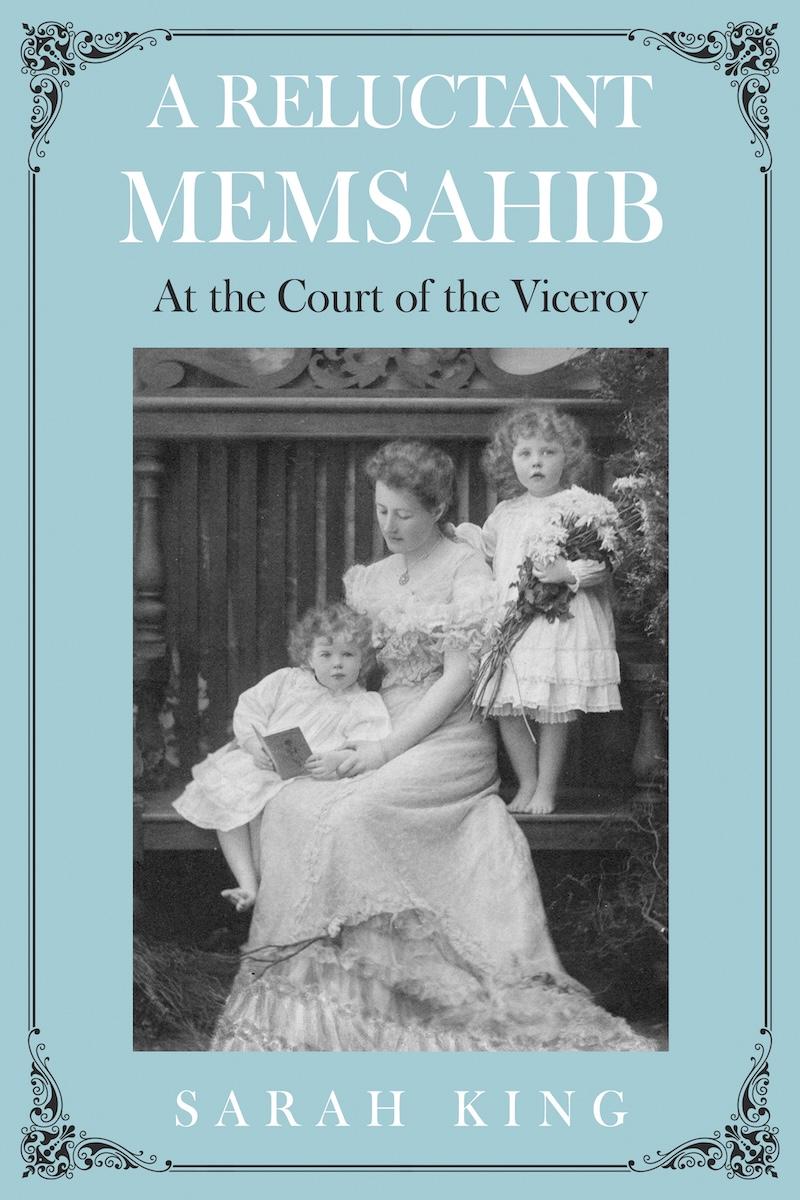

A Reluctant Memsahib

28th July, 2025

A Reluctant Memsahib

At the Court of the Viceroy

A Reluctant Memsahib shares the story of Isabel Richards, who travelled out to India in 1904 when her husband was appointed to the Viceroy’s Council. A lively correspondent with an eye for detail, and an ear for social nuance, Isabel wrote over 500 letters to her mother documenting her insights. This unique correspondence provides a ringside view of the key players and events over five years, which were amongst the most significant in the history of the British Raj with an impact still felt in India today.

Isabel’s letters and diaries provide a totally fresh impression of the extraordinary way the Indian Empire conducted itself, Not having worked their way up the ladder of the Indian Civil Service, the young couple were totally unprepared for life at the very top echelons of the British Raj. Seen through the fresh eyes of a liberally educated, middle-class London woman, she offers a first-hand account of Curzon’s battles with the India Office and Kitchener, and the hugely negative impact he had on Indians, which strengthened demands for Independence and helped set India on the road to partition. She takes nothing for granted and describes frankly what she saw, most especially the extraordinary social demands her husband’s role imposed on her and her struggle to balance this with her expectations as a mother.

Family Biography

Providing the Female Perspective

In his book Plain Tales from the Raj, Charles Allen observed that “few families were as packed with legends, both dead and living, as the Butlers.” Yet he omitted to mention any Butler women. History focuses on the big names and main events, but it’s often the experiences of people on the sidelines—including the women—that deepen our understanding of the past.

Hidden Contributions of Women

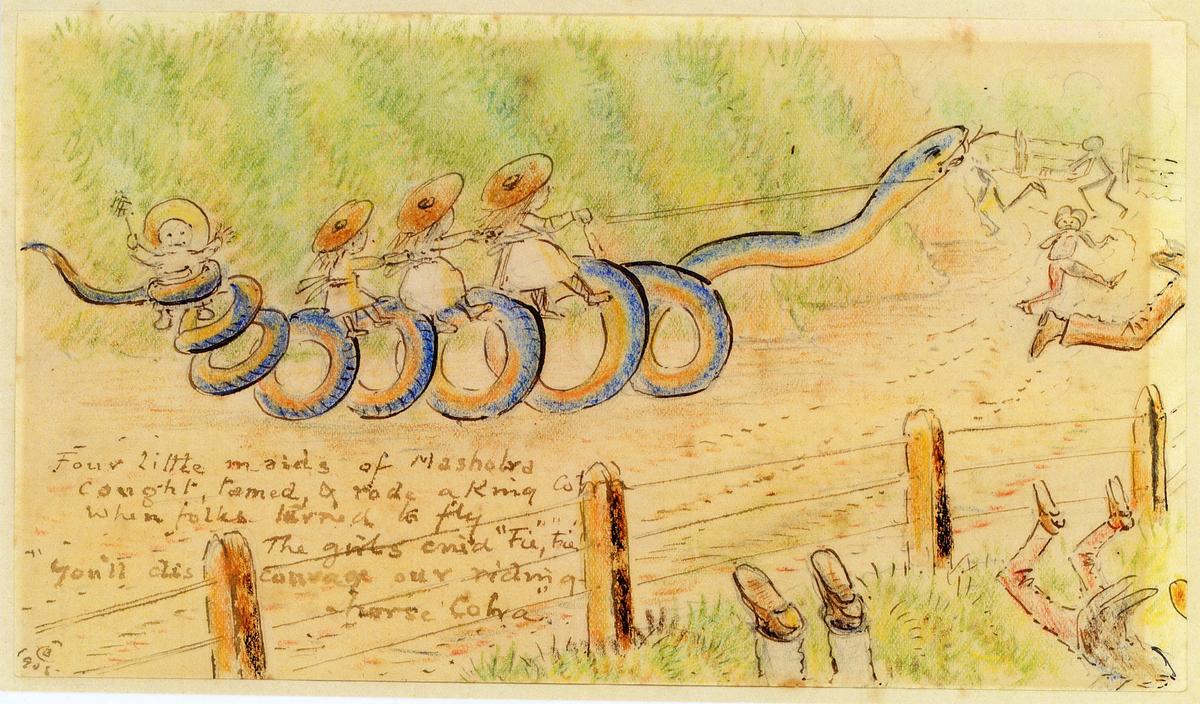

Rarely receiving a mention in the history books, the value of their contribution is often hidden from sight, with the only evidence stored in dust-covered boxes in an attic. This is what makes personal records like diaries, letters, and cherished family memories so valuable, providing vivid insights into the lived realities behind historical events.

Isabel’s Story

My great-grandmother Isabel’s letters and diaries, for instance, demonstrate this vividly; her correspondence and diaries capture the extraordinary transformation her life underwent as a young wife and mother when she was transported from genteel obscurity in London to a leading role at the highest level of Raj society during a dramatic period in India’s history.

Through her words, you can see how much her life changed when she moved from London to India—suddenly living among important people like Curzon, Kitchener, and Minto—but it’s the little details about her daily life that stand out most.

Why Family Stories Matter

Capturing family stories or writing a biography isn’t just about remembering those who came before us; it also helps us understand our history and how their values and decisions still affect us now. These histories remind us that the past isn’t just about famous people, but about everyone who played a part, even in quieter ways.

The British Empire

Good or bad?

Writing Isabel’s story it was all too easy to get distracted by commentary on whether the British Empire was a good or bad thing. One of the wonders of modern technology is how easy it is to investigate alternative views, but this only served to underline how little I know of the issues involved. Take the example of the politically incorrect Kipling who stoutly defended British colonisation, opposed Home Rule for Ireland, and openly criticised the Suffragette Movement in England. Having grown up loving his stories and poetry, I found myself pushing this aside to be open to Indian anger about his work stemming back to Isabel’s time. As recently as 2016, Mini Chandran wrote in the Indian Express, “Salman Rushdie seems to have summed up all of India’s attitude to Rudyard Kipling when he said ‘it is only with a mixture of anger and delight that we Indians can read Kipling. Anger at his obvious racism and delight at the felicity of his story-telling.’” It was as if I had come upon a sign saying “Writer Beware”! However important these issues are, they are not relevant to Isabel’s story, nor am I remotely qualified to make any such pronouncements.

Avoiding Presentism

Similarly, when writing about someone from the past and especially a family member, it is almost impossible not be biased, to see what one wants to see. The British women who went to India were part of a community that had a very clear sense of what it was. They were expected to enhance the imperial mission; to avoid letting the side down or behave in ways that could impact the authority of the Raj. Today we may or may not agree with that mission and see the expectations imposed by the community as absurd, but it would have taken a very strong or desperate woman to have said so at the time. It is easy to assume that these women were rather different from their modern counterparts, that with our improved understanding and empathy we would never have responded in the same way, but the reality is that we are all just as much the product of our times as they were of theirs. This is why, whilst important to publicly recognise past errors, it is also important to try and avoid “presentism” – judging historical events or figures by contemporary values and attitudes.

The Legacy of Empire

The truth is that like so much in history, the British Empire left a profound and complex legacy, with both positive developments and devastating negative consequences. Ultimately, while interpretations of the Empire's legacy will differ, the enduring value lies in what its history can teach us—and in how those lessons might guide us toward a future shaped by greater empathy, understanding, and progress.